China threatened to take “resolute countermeasures” if the leader of the small, democratically governed island of Taiwan meets U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy next week during her “transit visit” through the United States. It was the latest warning from Beijing amid escalating tension between the U.S. and China over Taiwan, which some analysts consider the most dangerous standoff between global superpowers, even as the war in Ukraine rages.

Here’s what you need to know about where things stand, and how we got here:

Why is there tension between Taiwan and China?

Taiwan is an island about 100 miles off the east coast of mainland China. It’s only a little larger than Maryland, but while that U.S. state is home to about 6 million people, Taiwan has a population of around 24 million.

Getty/iStock

For decades leading up to the end of World War II, Taiwan was controlled by Japan. Then it became part of the Republic of China, a country ruled at the time by nationalists known as the Kuomintang.

In 1949, after China’s civil war, Mao Zedong and his communist forces took over the Chinese mainland and the Kuomintang movement, led by commander Chiang Kai-shek, fled to Taiwan, where they set up a rival government. The U.S. maintained formal diplomatic relations with that government rather than Beijing until 1978, when it recognized the ruling Communist Party as China’s leadership and cut formal diplomatic ties with Taiwan.

Taiwan has continued to function since then as a multi-party democracy, however, separate from China’s communist government, and its domestic economy has flourished.

Over time, people in Taiwan — especially younger generations — have increasingly come to view themselves and their island as separate from the People’s Republic of China.

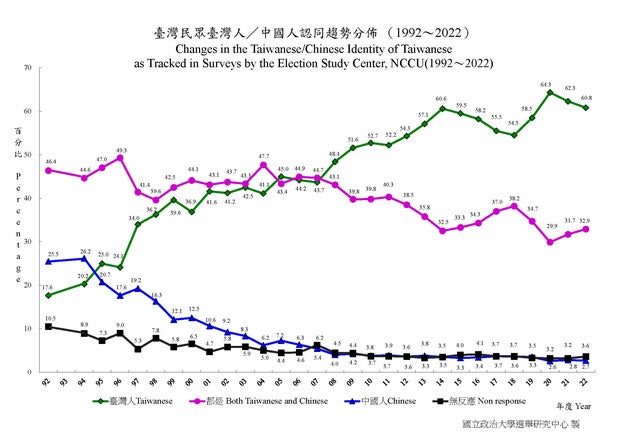

Election Study Center, National Chengchi University

Surveys conducted by the National Chengchi University show the percentage of Taiwanese people who consider themselves Chinese, as well as those who consider themselves both Taiwanese and Chinese, has decreased since the early 1990’s, while the percentage of people who consider themselves solely Taiwanese has increased.

The 2016 election of Tsai Ing-wen, who has always referred to Taiwan as an independent entity under the long-standing arrangement that allows the island to control itself, free of meddling from Beijing, was a clear indication of the changing mood on the island.

Tsai’s predecessor was an advocate for “unification” with mainland China, and he remains a leader of the pro-China political faction within Taiwanese politics, which considers unification with the mainland inevitable, and the only way of avoiding a catastrophic war.

China has always claimed sovereignty over Taiwan, considering it a breakaway province to eventually be brought under the control of Beijing under a “one country, two systems” principle, similar to how Hong Kong is administered.

SAM YEH/AFP/Getty

China exerts significant diplomatic pressure on other nations not to recognize Taiwan as an independent entity, and currently only 13 countries and the Vatican recognize it as a state.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has said “reunification” with Taiwan “must be fulfilled” — by force if necessary — and should not be passed down to future generations.

The Taiwan Relations Act and the U.S. stake

Tension between Taiwan and Beijing has always been high, but Xi’s vocal commitment to bringing the island under Chinese control has led many to believe the possibility of a military conflict is greater now than ever before.

As the cross-strait tension has increased, Taiwan has cultivated closer ties with the United States.

Taiwan produces the majority of the world’s most advanced computer chips, and it also sits along a chain of islands that include a number of U.S.-friendly territories of crucial importance to U.S. foreign policy, often referred to as the “first island chain.”

Under the Taiwan Relations Act, passed into law by the U.S. Congress in 1979, the United States is committed to supplying weapons to Taiwan “as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense,” but the act says nothing about whether the U.S. would be obligated to defend the island militarily if it were to come under attack.

Last year, President Biden raised eyebrows by saying the U.S. would send troops to help defend Taiwan “if in fact there was an unprecedented attack” by China. The island “makes their own judgments about their independence,” Mr. Biden told CBS News’ “60 Minutes” correspondent Scott Pelley, stressing that the U.S. was “not encouraging their being independent… that’s their decision.”

The United States has long employed a policy of “strategic ambiguity” over Taiwan, declining to explicitly state how Washington would respond to a Chinese invasion of the island. That appeared to have shifted under Mr. Biden, but the White House quickly denied any change in U.S. policy.

What’s happening now, and what comes next?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and China’s perceived backing of Moscow in the conflict, has heightened concern that Beijing could make a similar play to seize control of Taiwan.

Tsai is stopping in New York and Los Angeles this week and next on “transit visits” before and after formal visits Central America. It will be Tsai’s first time in the United States since the COVID-19 pandemic, but her seventh as Taiwan’s leader.

These “traveling visits” are generally managed carefully to avoid further inflaming tension between the U.S. and China.

Tsai may meet with McCarthy, a Republican lawmaker, in his home state of California. The congressional leader had expressed a desire to visit Taiwan, but the two reportedly agreed to hold a meeting in the U.S. because of Taiwanese security concerns.

McCarthy’s predecessor, Nancy Pelosi, visited Taiwan last year. Hers was the first visit to Taiwan by a house speaker in a quarter of a century, and it infuriated China. In response, the People’s Liberation Army staged huge military exercises in the area within days and, for the first time, fired ballistic missiles over Taiwan.

Beijing has warned that a meeting between Tsai and McCarthy, if it goes ahead, would be a move that “destroys peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait” and could cause a “serious confrontation.”

CBS News contributor General H.R. McMaster (Retired), who served as national security adviser to former President Donald Trump after a long career as an American battlefield commander, said recently that the U.S. military must “be ready” for a possible war with China.

- Is the U.S. in a “new type of Cold War” with China?

McMaster backed a memo that came from Air Force Gen. Mike Minihan, head of the U.S. Air Mobility Command, who warned that the U.S. and China could be at war within the next two years.

McMaster pointed specifically to Taiwanese elections scheduled for 2024, saying if China’s leadership “doesn’t see the outcome they want in Taiwan then, I think the chances go up.”

Most importantly, McMaster said, China’s leader Xi Jinping “has said he’s going to do it. You know, many of his speeches, he seems to be preparing the Chinese people for war, and of course, it’s our military’s job to be ready.”

The United States has said it hopes to see Tsai make a “normal, uneventful transit” through the country, and has urged Beijing not to overreact.

Haley Ott

Haley Ott is a digital reporter/producer for CBS News based in London.