Deep in the French countryside sits a medieval castle, Château des Milandes, with a most unlikely history. Akio, from Japan, and his brother, Brian, from the north African country of Algeria, have returned to visit the place they grew up with their siblings – 12 altogether – adopted from around the world.

The children, explained Josephine Baker years ago, “were all adopted to come down here to prove that human beings could live together. They might have different pigmentations and come from different continents, but that has nothing to do with the human being.”

They were known as the “Rainbow Tribe,” an experiment in racial equality devised by their legendary mother, one of the first Black entertainment megastars.

A showgirl extraordinaire, Baker took Paris by storm in the Roaring Twenties. As Walter Cronkite described in a 1960 CBS News documentary, “Paris in the Twenties,” “At the Folies Bergères, the rage is Josephine Baker. Daughter of a St. Louis washerwoman, her loose-limbed abandon epitomizes Paris at night.”

Baker grew up poor in the slums of St. Louis. As a young dancer, she made it as far as New York, and then beyond, with an American vaudeville show to Paris in 1927. At the time, segregation and racism limited opportunities for Black performers in America. But in France, there was at least no legal segregation.

Baker rocketed to fame across Europe with her exuberant style, and a then-scandalous dance, wearing only a tiny skirt of bananas. On stage she was playing to a racial trope, but in life she was impossible to stereotype.

According to University of California, San Diego professor and director of African and African-American Studies, Bennetta Jules-Rosette, “In addition to her performing, she is a businesswoman. She has a hair cream called Bakerfix. Her picture is going on actual bananas because of her banana skirt. So, not only then is she a music hall star, a movie star, but she is an entrepreneur.”

And, believe it or not, a spy working with the French against the Nazis in World War II.

“She could also fly a plane, so she was actually an Air Force pilot,” Jules-Rosette told correspondent Elizabeth Palmer.

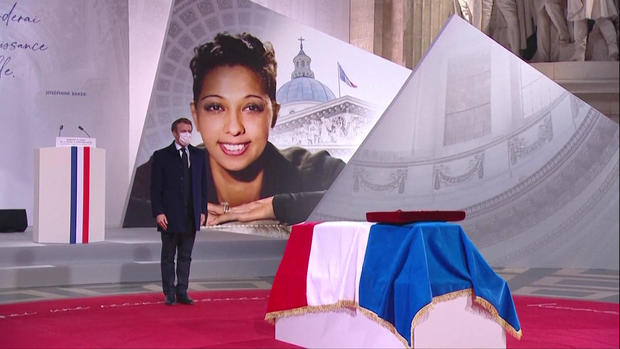

On Wednesday in Paris, Baker was awarded France’s highest honor: The first Black woman to be inducted into the Panthéon mausoleum, more than 45 years after her death.

French president Emmanuel Macron hailed her as a war hero, entertainer, a civil rights fighter, and of course, a mother.

One of her sons, Brian Bouillon Baker, met Palmer at the castle to give her a tour, and to reminisce.

“So, it was like a fairy tale to live in a castle?” asked Palmer.

“Yes, it was like the holidays,” Baker replied.

He pointed out photos of his siblings: “There is Luis, a Colombian. Jari from Finland. My brother, Kofi, from Ivory Coast.”

The Rainbow Tribe was more than a family for Baker; it was a living commitment to her ideals: “Showing to the world that when kids, babies grow up together from all kinds of continents and countries and cultures and religions, they can live together,” he said.

Palmer asked, “What would you say your mother’s legacy is?”

“Her ideal of universal brotherhood; it was very important for her,” he replied.

Baker would eventually return on tour to the U.S., where she was among the first to insist on integrated audiences. Jules-Rosette said, “Many people credit Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack with desegregating Las Vegas. But Josephine was the first performer at the Flamingo Club requiring the club to be desegregated.”

In an archived interview, a reporter asked Baker if she thought she would “serve your race” far better if she had remained in the U.S.

Baker: “My race? Reporter: “The Negro race.” Baker: “Ah ha. You see, I think a little differently. For me there is only one race: The human race.” Reporter: “How long are you going to stay?” Baker: “You want me to stay, don’t you?” Reporter: “I’d like you to stay. I think you could help the Negro movement in the United States.” Baker: “Oh, don’t say that.” Reporter: “Why not?” Baker: “Because it’s not a Negro movement. It’s an American movement.”

Her role in that movement earned her an invitation to join Martin Luther King Jr. to speak at the historic March on Washington :

“You know, friends, that I do not lie to you when I tell you I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents, and much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth. And then look out, ’cause when Josephine opens her mouth, they hear it all over the world.”

Josephine Baker died in Paris of a stroke in 1975. Crowds poured into the streets as she was buried with full military honors – a salute to her life and her legacy.

Palmer asked Jules-Rosette, “Where did she get that kind of self-possession and recognition of her own power?”

“I think it was innate – an innate poise and an innate self-confidence,” she replied. “Her legacy, I think, is one of courage … courage in the face of adversity and all of the things that she was able to overcome in her lifetime.”

And like all truly great performers, she made it look easy.

Monsieur et madame, vive la Josephine Baker!

For more info:

- “Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and the Image” by Bennetta Jules-Rosette (University of Illinois Press), in Trade Paperback format, available via Amazon and Indiebound

- Bennetta Jules-Rosette, University of California, San Diego

- Pantheon (Paris Convention and Visitors Bureau)

- Official site of Josephine Baker

Story produced by Mikaela Bufano. Editor: Brian Robbins.