Cybersecurity responders are working around the clock to shore up networks hit by last week’s hack of Microsoft’s Exchange email service — an attack that has impacted hundreds of thousands of organizations worldwide.

On Friday, the White House urged victims to patch systems and stressed the urgency: The window for updating systems could be measured in “hours, not days,” a senior administration official said.

“This is a crazy huge hack,” Christopher Krebs, former director of the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), tweeted last week .

The fallout from the hack is still being measured. President Joe Biden has been briefed on the attack, and discussed it with leaders from India, Japan and Australia at a summit Friday, said National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan. The National Security Council has assembled a multi-agency government task force to address the massive breach.

The breach follows last year’s Russian-linked hack, which leveraged SolarWinds software to spread a virus across 18,000 government and private computer networks.

” Solarwinds was bad. But the mass hacking going on here is literally the largest hack I’ve seen in my fifteen years,” said David Kennedy, CEO of cybersecurity firm TrustedSec. “In this specific case, there was zero rhyme or reason for who [attackers] were hacking. It was literally hack everybody you can in this short time window and cause as much pandemonium and mayhem as possible.”

Here’s what to know about the Microsoft Exchange exploit:

When did the attack start?

Hackers began stealthily targeting Exchange servers “in early January,” according to cybersecurity firm Volexity , which Microsoft credits for identifying initial exploits.

According to Microsoft corporate vice president Tom Burt , hackers first gained access to an Exchange Server either with stolen passwords or by using the previously undiscovered vulnerabilities used to “disguise itself as someone who should have access.” Using web shells, hackers controlled servers through remote access – operated from U.S.-based private servers – to steal data from a victim’s network.

Who is behind the attack?

Microsoft identified a Chinese-based group known as “Hafnium” as the primary actor behind initial attacks.

The Hafnium group has historically targeted “infectious disease researchers, law firms, higher education institutions, defense contractors, policy think tanks and NGOs,” Burt wrote in a company blog post .

How did Microsoft respond?

Microsoft made the vulnerabilities public on March 2, and released “patches” for multiple versions of Exchange. While Microsoft typically launches updates on the second Tuesday of each month – known as “Patch Tuesday” – its announcement came on the first Tuesday of the month, an indication of the urgency.

Days later, the company also took the unusual step of releasing security patches for out-of-date versions of Exchange Server.

A Microsoft spokesperson told CBS News that the company was working closely with CISA, other government agencies and security companies. In a statement provided to CBS News last week, the company said, “The best protection is to apply updates as soon as possible across all impacted systems. We continue to help customers by providing additional investigation and mitigation guidance. Impacted customers should contact our support teams for additional help and resources.”

How did the attack evolve?

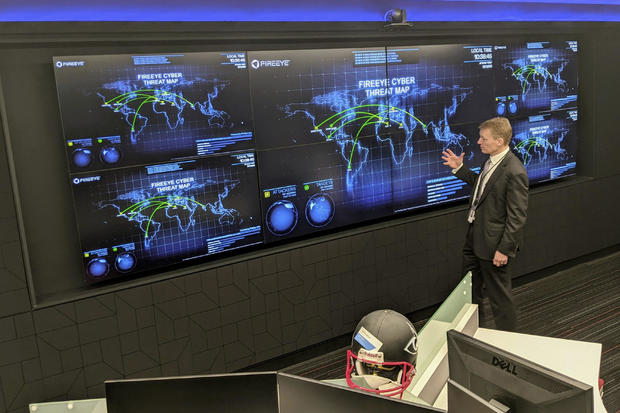

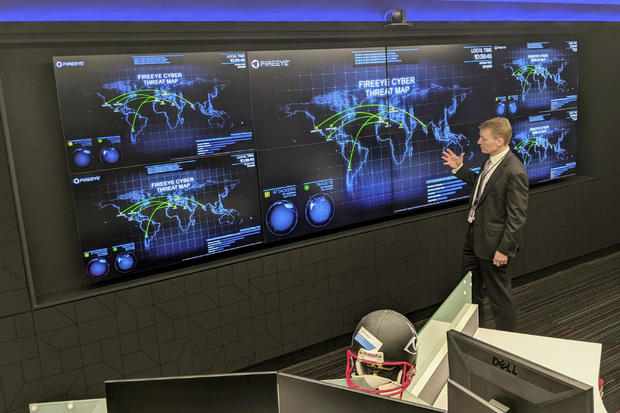

Experts say it’s common for hackers to step up an attack immediately preceding a fix, but that the pace was much faster in this case. “Once a patch is imminent, [hackers] may turn to wider exploitation because there’s this ‘use it or lose’ it factor,” said Ben Read, the director of threat analysis at the cybersecurity company Mandiant.

But in late February, just days before Microsoft released its security patch, security researchers saw an automated second wave of attacks targeting victims across industry sectors.

“They went very aggressive, essentially hacking everybody,” Kennedy said. Hackers planted backdoors known as “web shells” in systems, launching attacks against organizations “without rhyme or reason.” Kennedy added, “We haven’t seen that from China in the past.”

Microsoft said Friday it is investigating whether attackers were tipped off that a patch was imminent. The internal probe centers on “what might have caused the spike of malicious activity” at the end of February, but investigators have not yet drawn any conclusions. “We have seen no indications of a leak from Microsoft related to this attack,” a Microsoft spokesperson told CBS News.

What did the hackers want?

The goal of the hackers is unclear. “Tens of thousands of targets, most of which really don’t have any intelligence value,” said Read. “They’re just sort of small towns and local businesses. Their information likely does not have any value to the Chinese government.” Read called the “level of mass exploitation” of haphazard bystanders a “very rare” show of force.

And what began as a hack led by Chinese hackers soon gave way to a feeding frenzy from criminal gangs in other countries, including Russia.

At least 10 criminal espionage groups have exploited the flaws in the Exchange Server email program worldwide, antivirus firm ESET said in a blog post Wednesday .

Who was targeted?

Cybersecurity experts tell CBS News that tens of thousands of private and public U.S. entities have been hit. “Initially, early estimates were 30,000 people were hacked. We’re seeing a number now that is much higher,” Kennedy said. “Globally, it’s definitely in the multi-hundreds of thousands of servers that were hacked.”

The list of victims worldwide continues to grow to include schools, hospitals, cities and pharmacies.Cybersecurity firm CyberEye identified “an array of affected victims including U.S.-based retailers, local governments, a university, and an engineering firm” in a blog post.

The European Banking Authority, the banking regulator for the E.U., announced it had been hit.

The attack largely steered clear of Fortune-500 companies and large organizations that have migrated their servers to Microsoft Exchange Online – Microsoft’s cloud-based email and calendar service. But the widespread attack will prove painful to smaller companies that run Microsoft exchange on their on-premises servers and can least afford high-end security.

“The most concerning victims by far are small- and medium-sized businesses who don’t follow security news everyday, who may not be aware that there is this massive patch,” Katie Nickels, director of intelligence for cybersecurity firm Red Canary, told CBS News. She added that victim notification has presented a “huge challenge” given the large number of affected organizations. “The thing that worries me most is everyone that we don’t see,” she said.

Has the federal government been breached?

Officials have not confirmed breaches of any federal agencies, Eric Goldstein, executive assistant director of CISA’s cybersecurity division told lawmakers last week. “At this point in time, there are no federal civilian agencies that are confirmed to be compromised by this campaign.”

But National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said Friday the federal government is “still trying to determine the scope and scale” of the hack.

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) said the breach “poses an unacceptable risk to Federal Civilian Executive Branch agencies,” and issued an emergency directive on March 2 ordering all agencies to immediately implement a patch or disconnect from Exchange Server, if impacted.

What’s the risk?

Cybersecurity firms say they have begun to observe hackers stealing passwords from networks and installing cryptocurrency mining malware on servers.

And Microsoft said in a late-night tweet Thursday that it had detected a new strain of “ransomware” – a kind of malicious software designed to block access to a computer until the victim pays a sum of money.

While companies may assume their system is fixed once they install Microsoft’s security patch, the emergency update does not expel attackers from servers, leaving already breached organizations susceptible to further exploitation.

“There’s also a lot of concern now that China is going to be selling these accounts off” to bad actors, including “ransomware authors to inflict as much damage as possible,” Kennedy said. “So right now is a very critical period for us.”

Is this connected to Solarwinds?

The latest attack is not connected to last year’s SolarWinds breach, though the timing of two massive, consecutive cyber hacks has strained the ability to respond.

“The big impact on the industry is timing,” Nickels said. “We’re a year into a pandemic. People are working remotely, and they’re exhausted and stressed.”

U.S. officials tell CBS News that while the SolarWinds hack has more national security implications given the fact that hackers in that attack accessed nine federal agencies, the attack by Microsoft is far more widespread.

“This is definitely bigger than Solar Winds,” Kennedy said. “While [SolarWinds] was bad, it didn’t hit near the breadth of systems here.”

“This hack is much noisier and much easier to detect, but the scale is what makes this so concerning,” Nickels said.

Senior White House administration officials told reporters Friday that the Biden administration will announce executive action in the wake of the SolarWinds attack. The White House is also unveiling a new executive order on cyber in “the next few weeks,” which includes a proposal to assign letter-grade cybersecurity ratings to software vendors used by the federal government.

It remains unclear if the upcoming cyber executive order will also address risks posed by the latest Microsoft Exchange hack.

Both Russian and Chinese officials have denied responsibility. Last week, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin said China “firmly opposes and combats cyber-attacks and cyber theft in all forms.”

Margaret Brennan contributed to this report.