In the Arctic, where the reliable supply of energy can mean the difference between life and death, one community is leading the way in one of the planet’s most unique renewable energy transitions.

For more than 100 years, the economy of Svalbard, Norway — a group of islands near the North Pole — has revolved around coal mining. But burning coal warms the planet, which contributes to the climate change that is now melting Svalbard’s glaciers.

The Norwegian government has now mandated Svalbard close its last coal mine within two years.

“We’re proud of the mining industry,” said Heidi Theresa Ose, CEO of the coal mining company, Store Norske. “At the same time, we’re now looking into the future and finding new ways to contribute with energy.”

CBS News traveled to the world’s northernmost and fastest-warming community of Svalbard. What scientists are learning there helps Americans understand the changes happening in the United States. As the Arctic warms, it adds to rising sea levels along our coasts and instability in the atmosphere that contributes to our extreme weather events.

While Svalbard intends to transition to renewable energy, there’s very little data on how well wind and solar can perform in the islands’ harsh winter conditions, where there’s no sun for months at a time.

Renewables in the Arctic

In a place as cold and remote as Svalbard, any disruption to the off-grid power supply could require a total evacuation of its 2,500 residents to mainland Norway, which is 600 miles away by boat or plane.

With that in mind, Store Norske has partnered with scientists at the University Centre in Svalbard to begin reliability testing of the world’s northernmost solar park, on the site of Isfjord Radio, a remote luxury hotel. The hotel runs on generators powered by diesel fuel.

“We don’t have a lot of experience of how (the technology) can handle the rough climate and weather conditions that we have up here,” Ose said. “We have a job to verify the technology in the Arctic climate.”

Store Norske reports strong results from its 360 solar panels. In summer, when the sun shines for 24 hours, the panels supply all the power needed to operate the hotel.

In spring, the company learned the panels can collect both direct sunlight and light that bounces off the snow. Ose said while fuel is still needed in the total darkness of winter, the hotel has been able to cut diesel consumption by 70%.

The next testing ground will be the town of Longyearbyen, population 2,500, which is considered the northernmost community in the world. In October, it stopped burning coal at its power plant and transitioned to cleaner, but still dirty, diesel fuel. The town intends to add renewables to Longyearbyen’s energy mix as those technologies are proven reliable in the Arctic.

In addition to Longyearbyen, there are about 1,500 communities above the Arctic Circle, where people live off-grid. Store Norske plans to sell its renewable energy solutions to those communities, which include settlements across Canada and Alaska.

“If you put all these 1,500 (communities) together, then you have something really big altogether that would have an impact,” said Anna Sjöblom, a meteorologist at the University Centre in Svalbard, who is collaborating on the project.

Avalanche protection technology

Beyond renewable energy, Longyearbyen is also where Store Norske and the University Centre in Svalbard have developed new technology to help predict another threat to the community’s well-being — avalanches.

While winters are very cold, snowfall is generally light. But in January of 2015, a major storm hammered the island with blinding wind and snow. More than 16 feet fell in about 12 hours in some spots.

These rare conditions triggered an avalanche on one of the town’s mountains — the first to ever do serious damage to Longyearbyen. The snow ripped homes off their foundations and left them in a pile. Two people died, including a young girl.

“I knew the girl,” Line Nagell Ylvisåker, Editor of the Svalbard Post newspaper, remembered. “She went to kindergarten with my daughter. So, it was really close and hard to understand that it happened.”

Since that fatal avalanche, Martin Indreiten with the Artic Safety Center at the University Centre in Svalbard, has led the effort to defend the community against the threat of future avalanches.

Indreiten said the risk of an avalanche has always been reliably highest in the spring, but as Svalbard warms, now they can happen at other times of the year, as well.

“It’s the uncertainty,” Indreiten said. “You don’t know,”

Norway spent $25 million to build a dam at the bottom of the mountain to stop tumbling snow and protect the town. Higher up on the mountain, it built avalanche fences that help keep the snow from sliding down.

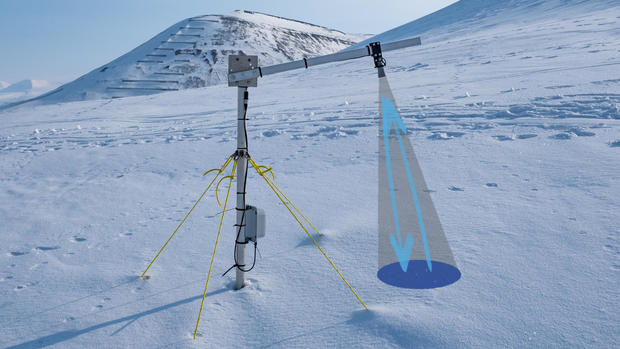

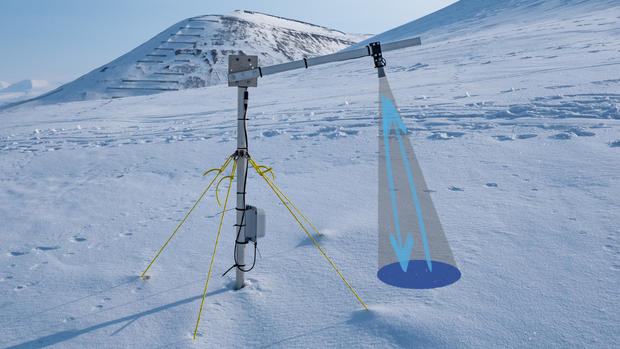

Indreiten designed an early-warning system that would give people time to evacuate. Working with the Norwegian mobile company Telenor, Indreiten and his colleagues developed the low-cost snow senor.

The devices are installed in remote locations. They bounce a beam off the snow to measure its depth and sends back hundreds of measurements each day. Each device can last up to 10 years on a single battery and costs just $600.

CBS News

“We are getting information from the places we want to get information, and the cost is so low that many can use it,” said Indreiten.

Avalanches are a problem in communities around the world. In the U.S. each winter, 25 to 30 people die in avalanches, mostly in national forests, according to the National Avalanche Center.

Indreiten hopes the new technology can be useful worldwide. It has already been installed in another avalanche-prone community on mainland Norway.

“If you have better tools to do forecasting, then we could move people out of harm’s way when it’s necessary to do it,” Indreiten said.

Take an adventure to Svalbard, Norway in this special interactive web page and learn how climate change is impacting communities across our country.

Meet our experts

Martin Indreiten collaborated on an early warning system to protect the community of Longyearbyen from the threats of future avalanches. His team at the Arctic Safety Center built low-cost, snow depth sensors that are now deployed on the steep slopes around town. Each device sends back hundreds of measurements a day, giving safety managers better insights into avalanche risk and when to issue evacuation orders. Indreiten believes avalanche-prone communities around the world will benefit from the technology developed on Svalbard.

David Schechter

David Schechter is a national environmental correspondent and the host of “On the Dot with David Schechter,” a guided journey to explore how we’re changing the earth and earth is changing us.