Perla, 46, a Nicaraguan political dissident, has been living with her daughter and grandchildren in a squalid migrant tent camp in the Mexican border city of Matamoros for a year and half.

A former local councilwoman who was threatened for publicly opposing Daniel Ortega’s regime, Perla is waiting for a U.S. immigration judge to adjudicate her asylum request, with her final court hearing postponed indefinitely due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“It’s been really difficult. You don’t know what can happen to you here,” she told CBS News in Spanish. “We try to make the most of it, but we have to deal with the rain, the sun and the bathrooms that are not clean.”

Perla said the encampment is not a place for children like her granddaughters, who are 10 and 7 years old. “Not a day goes by without me crying, without me saying, ‘I want to leave,'” she said.

For nine months, Angela, 24, and her family have been stranded in Reynosa, another Mexican border town and hotspot for turf wars between warring cartels. The Honduran mother crossed the U.S. border with her partner and toddler in March and had a baby girl at a hospital in McAllen, Texas, while in Border Patrol custody, according to medical records.

After her daughter’s birth, Angela and her family were not allowed to stay in the U.S. Instead, they were expelled to Mexico without a court hearing under a pandemic-related measure authorized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) last spring, according to lawyers.

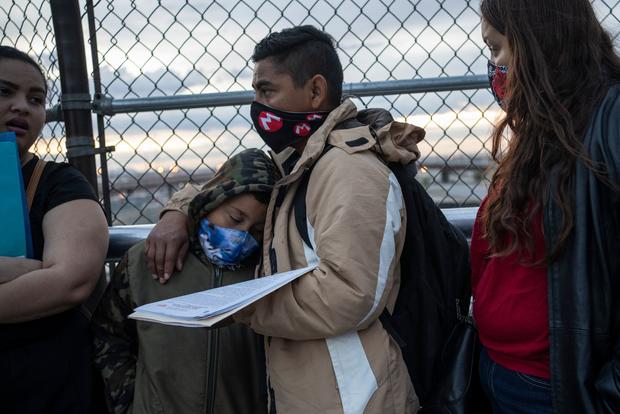

Thousands of asylum-seekers waiting at America’s doorstep face similar predicaments as a result of a network of policies the Trump administration implemented to deter would-be migrants, whom it accused of gaming the country’s humanitarian programs to gain easy entry into the U.S.

President Biden decried these measures as “inhumane” and vowed to end them during the campaign, accusing the Trump administration of forcing asylum applicants to live “in squalor.” After winning the election, his advisers said unwinding the many policies would take time, largely due to the pandemic.

During Mr. Biden’s first day in office, his administration stopped placing asylum-seekers in the so-called “Remain-in Mexico” program. He is also set to formally end the policy and other asylum limits this week as part of an executive order to retool how U.S. border officials will process migrants going forward.

But the new administration continues to use the Trump-era CDC order to quickly expel migrants — including families with children — without allowing them to request U.S. refuge, according to court documents and interviews with attorneys. The government has also not said whether it will allow the estimated 20,000 migrants in Mexico with pending asylum applications to continue their cases inside the U.S.

Mr. Biden has yet to publicly order a review of the expulsions order, despite a pledge made by his campaign. The CDC deferred requests for comment to the White House, which did not offer any. U.S. diplomats have instead been warning would-be migrants in Central America that the expulsions will continue indefinitely.

“Under the currently operational CDC order, certain individuals encountered at the border, including those encountered while attempting to enter the United States between ports of entry, are subject to expulsion during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Department of Homeland Security spokesperson Matt Leas said in a statement to CBS News on Sunday.

The Biden administration’s continuation of Trump-era border policies, even if short-lived, has left thousands of asylum-seekers stranded in dangerous Mexican towns or facing swift expulsion to the countries they fled. Many are hopeful that their fortunes will change under a new U.S. administration — but it’s unclear when and if that may happen.

“I can’t return to Cuba,” Jesús, 47, an asylum-seeker waiting in Matamoros for his U.S. court hearing, told CBS News in Spanish. “God willing, Biden’s government will understand us.”

Jesús said he fled Cuba in 2019 after being discriminated by the government there because of his identity as a gay man. He said he does not feel safe in Matamoros, a crime-ridden city located in the state of Tamaulipas, which carries a “Do Not Travel” warning from the U.S. State Department.

“Flatly illegal”

By continuing the border expulsions, the Biden administration is also enforcing a policy implemented under political pressure that has so far failed to pass legal muster in court.

While the Trump administration said the directive was designed to protect immigration agents and the U.S. public from migrants who may be infected with the coronavirus, three former government officials who worked on public health issues told CBS News last fall that the Trump White House pressured former CDC director Robert Redfield to sign it over objections from agency experts.

One former CDC official said the agency was “forced to do it,” while another called the policy a “misappropriation” of public health laws.

Three federal judges have also concluded that the late 19th-century public health authority the Trump administration invoked does not authorize expulsions.

Lee Gelernt, a civil rights lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union, sued the Trump administration over the expulsions, and convinced a federal judge in November to prohibit the government from expelling unaccompanied children. On Friday, however, an appeals court lifted the injunction.

Asked if border officials will resume expelling unaccompanied migrant children in light of Friday’s court order, Leas, the DHS spokesperson, said he could not comment “due to ongoing litigation.” The Justice Department declined to comment.

Gelernt filed another lawsuit earlier this month seeking to halt the expulsion of migrant families who the ACLU said could face persecution if expelled. According to filings in the case, asylum-seeking parents and children as young as 23 months old continue to face expulsion, even since Mr. Biden took office. Gelernt said the policy should be scrapped in its entirety, and vowed to continue suing the government unless Mr. Biden ends the practice.

“It is flatly illegal and was enacted by the Trump administration as a pretext to shut the border, despite the view of medical experts that it was unnecessary from a public health standpoint,” Gelernt told CBS News.

Andrea Meza, an attorney with the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services, is currently helping a group of parents and children detained at a family detention facility in Karnes City, Texas. Immigration and Customs Enforcement confirmed the facility is being used to hold families facing expulsion. Like Gelernt, Meza called on the Biden administration to act quickly.

“Each day that Biden fails to rescind the use of Title 42 for pretextual border enforcement means more families expelled to the dangerous situations from which they fled,” Meza told CBS News, using the government term for the expulsion process.

Lawyers are not the only ones calling for an end to the expulsions. U.S. government asylum officers recently told their leadership at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services that the policy should be discarded, saying it was enacted “under the guise of public health measures,” according to a white paper authored by the officers’ union.

Last week, 89 public health experts sent a letter to Rochelle Walensky, Mr. Biden’s CDC director, urging her to rescind the order that has authorized the border expulsions, denouncing it as a discriminatory edict with “no scientific basis.”

“Rather than subverting public health principles to ban people seeking protection from harm, the CDC should rescind the October 2020 order and put in place effective, science-based measures to safely process asylum seekers and others seeking protection,” the experts wrote, outlining several recommendations for border officials.

Angela, the young mother who was expelled alongside her family last spring, said they left Honduras after gang members tried to recruit her partner. Life in Mexico with a 4-year-old and infant has not been easy, she added.

“It’s very dangerous here. You can’t even go outside,” Angela said in Spanish, citing cartel violence and kidnappings.

Lawyers with the group Al Otro Lado are preparing to ask the Biden administration to parole Angela and her family inside the U.S., arguing that her infant was illegally expelled since she was born on American soil, and U.S. citizens are supposed to be exempt from the expulsions order.

“What they did to us was illegal,” Angela said.

In Matamoros, Perla, the asylum-seeking grandmother from Nicaragua, said she believes the Biden administration will help her family and other migrants waiting in Mexico.

Perla attributed her cautious optimism to first lady Jill Biden’s visit to Matamoros in December 2019. “She knows the conditions we’re enduring,” Perla said, recounting a conversation she said she had with the first lady.

“That’s the hope we have. That he’ll get us out here soon,” she said, referring to the president. “After being here on the banks of the river for a year and a half, as a human being, I would not wish this on anybody.”

Editor’s note: Perla and Jesús asked for their surnames to be omitted because they have pending U.S. asylum cases. Angela’s representatives asked for her name to be changed to protect her identify.