The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has suggested Britain’s drug regulator may be gambling with public safety by expanding the time gap between administration of the first and second doses of Pfizer’s coronavirus vaccine beyond that proven safe and effective by trial data. The FDA warned in a statement on Monday that there was a “potential for harm” if people believed they were protected against COVID-19 by a first dose of Pfizer’s vaccine for longer than available data demonstrate.

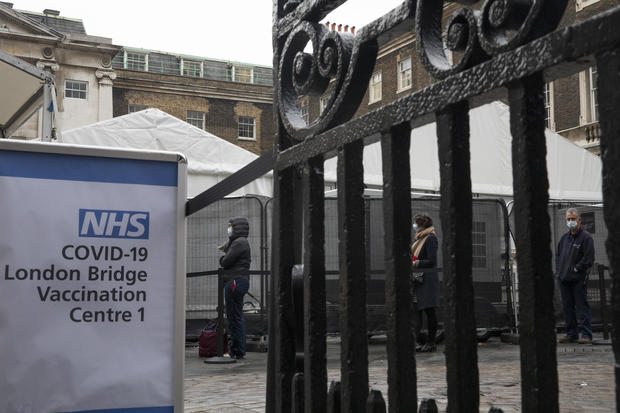

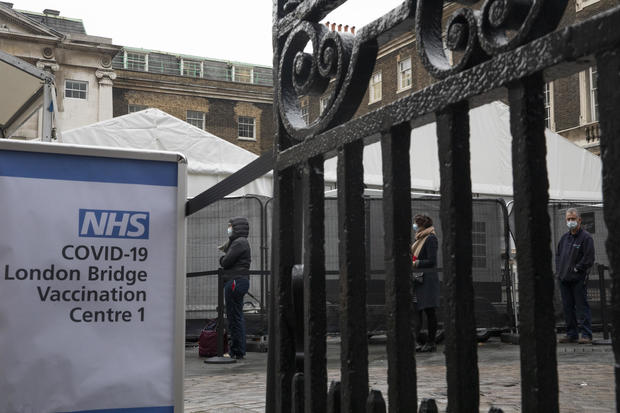

Facing a dramatic surge in both infections and hospitalizations — fueled, according to U.K. officials, by a more infectious strain of the coronavirus discovered in southeast England — British officials decided last week to change their inoculation strategy .

- Will vaccines work on South Africa COVID strain?

The focus is now on getting as many people as possible a first dose of either the Pfizer shot or the other approved for use in the U.K., developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca. Under government policy, the second doses of both vaccines can be put off for up to 12 weeks.

Oxford scientists have said their trial data supports allowing a window of up to 12 weeks between shots, and that their vaccine will provide protection to the full extent possible (up to 74% effective at preventing COVID-19 infection) for that full period.

- FDA considers halving Moderna vaccine doses

Pfizer hasn’t said that, however. Along with it’s German partner BioNTech, the American pharmaceutical maker has made it clear that their trial data only shows efficacy for 21 days after a first dose.

The U.K. regulator appears to be making an assumption based on the available data from the Pfizer/BioNTech Phase-3 human trials.

“The decision was made to update the dosage interval recommendations for the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine following a thorough review of the data by the MHRA’s COVID-19 Vaccines Benefit Risk Expert Working Group,” a spokesperson for the U.K.’s Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency told CBS News on Tuesday.

The spokesperson said the Working Group “concluded that vaccine efficacy will be maintained with dosing intervals longer than 21 days… based on clinical trial data that showed the vaccine was 90.5% effective against preventing COVID-19 after the first dose once the protection that starts at around 12 days kicks in, and there was no evidence to suggest that the effectiveness of the vaccine is declining towards the end of the 21-day period following the first dose.”

But as the FDA and Pfizer have said, there’s also no data to show that the effectiveness of the first dose lasts until the 12-week mark, or anything near it. The FDA approved the Pfizer vaccine for emergency use with a maximum of 21 days between the first and second doses.

“Suggesting changes to the FDA-authorized dosing or schedules of these vaccines is premature and not rooted solidly in the available evidence,” the U.S. agency said in its statement. “Without appropriate data supporting such changes in vaccine administration, we run a significant risk of placing public health at risk, undermining the historic vaccination efforts to protect the population from COVID-19.”

“If people do not truly know how protective a vaccine is, there is the potential for harm because they may assume that they are fully protected when they are not, and accordingly, alter their behavior to take unnecessary risks,” the FDA warned.

With the worst COVID-19 epidemic in Europe, and one that is worsening fast, Britain’s strategy was clearly born of urgency. It’s a bid to provide as many people with some immunity as fast as possible to try and stem the dramatic spread of the virus, and it the U.K. isn’t alone in considering the measure.

German Health Minister Jens Spahn confirmed this week that the government was considering extending the length of time between the first and second doses of the Pfizer vaccine, which was developed in conjunction with German firm BioNTech, citing the example set by the U.K.

Spahn stressed, however, that the Health Ministry would await guidance from the Standing Committee on Vaccination at the national health agency, the Robert Koch Institute, before making a final decision.